Kepler’s Giant Exoplanet Candidates — Real or Not?

A new study shows that about half of Kepler’s giant exoplanet candidates aren’t real planets. Astronomers expected this.

In the midst of a slew of exoplanet results from the Extreme Solar Systems III conference in Hawai‘i last week, one study garnered a lot of attention following a press release headline that read: “Half of Kepler’s Giant Exoplanet Candidates are False Positives.”

The study at the heart of the hubbub was a follow-up on potential giant planets detected by NASA’s Kepler satellite, which over four years found exoplanet candidates by the thousands. It turns out that a large number — roughly 55% of Kepler’s list of giants, the study authors say — might not be planets after all.

That might sound shocking. But it’s not: these results were largely expected.

The Study

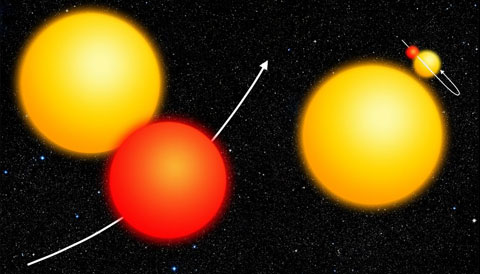

Two common false positives that plague Kepler data: the signals of grazing eclipse binaries (left) and background eclipsing binaries (right) can mimic the signal of a giant planet transiting its star.

NASA / Ames Research Center

NASA / Ames Research Center

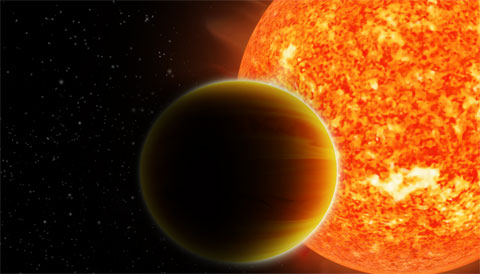

Alexandre Santerne (University of Porto, Portugal, and Aix Marseille University, France) and colleagues followed up on Kepler’s long list of planet candidates during a five-year observing campaign with the 1.93-meter telescope at the Observatory of Haute-Provence in France. Kepler detected planets by their transits, the slight dimming of a star’s light they cause when they pass in front of it. Using the SOPHIE spectrograph, Santerne’s team sought to confirm these starlight dips’ planetary status by measuring the worlds’ tiny gravitational tugs on their stars. The instrument could detect radial-velocity wiggles as small as 2 meters per second.

Small planets cause too weak a wiggle for SOPHIE to discern, so the team could only follow up on giants. Rather than choosing targets based on a candidate’s radius, whose measurement can be uncertain, the team chose targets by their transit depth: the larger the planet, the more light it will block. They also chose only those planets with orbits taking less than 400 days.

In the end, Santerne and colleagues spent 370 nights between July 2010 and July 2015 observing 129 of Kepler’s more than 4,000 planet candidates.

Of these, only 45 turned out to be bona fide planets. The rest were brown dwarfs (3) or multiple-star systems (63, 48 of which were eclipsing binaries); for an additional 18 cases the team could reject both these alternatives but still couldn’t confirm the planet. Even if all of those 18 cases turn out to be planets, 51% of Kepler’s giant potential planets would still turn out not to be real.

That’s a lot higher than what previous studies have found. Most recently, Francois Fressin (Harvard University) and colleagues found a 20% false-positive rate for giant planets.

A higher “fake” rate could have implications not just on the tally but on our understanding of these worlds. For example, once they removed false positives from the group, Santerne’s team saw three distinct populations of giant planets: hot Jupiters that orbit their star in a few days, temperate giants more like those in our own solar system, and a third type with orbits in between. Other studies based on the Kepler candidate list haven’t recognized these separate populations because their samples were too contaminated, Santerne’s team argues.

No Surprise

Santerne’s work is important: it’s the largest radial-velocity study of Kepler planet candidates conducted so far. But is the high false-positive rate really surprising? Not at all, says Tim Morton (Princeton University), an expert on Kepler data.

“The reason this apparent false-positive rate from this study is so high is mostly because the Kepler team has been very generous with the last few data releases with what has been called a "candidate’,” Morton says.

In the early years, explains Kepler mission scientist Natalie Batalha (NASA Ames), the Kepler team automatically marked any potential planet with more than twice Jupiter's radius as a false positive. But Kepler couldn't always measure planet sizes with a high degree of accuracy. Moreover, the team worried that they were throwing away objects in the divide between planets and the failed stars known as brown dwarfs.

So the Kepler team stopped throwing out planet candidates based on size alone, which increased the number of "fakes", but now enables scientists to study the occurrence rate of brown dwarfs and compare it against that of giant planets.

So Batalha sums up the study differently than the news headlines did. Santerne's team found that warm Jupiters, Jupiter-size giant planets no farther from their parent star than Earth from the Sun, are 15 times more common than brown dwarfs in similar orbits, she says. "THAT is the real news!"

Morton, in turn, is in the process of calculating the chance that each planet would turn out not to be real for every potential planet in Kepler’s list. His results are due out soon. But he has already compared his calculations against Santerne’s observations and found they match up. Researchers will use Morton's calculations and Santerne's follow-up observations to decide which potential planets to include in future studies of, for example, giant planet populations.

Morton also stresses that the Santerne results are specific to giant planet candidates — all indications are that the false-positive rate for smaller candidate planets is still low.

No comments:

Post a Comment