Where and When Will Rosetta Crash?

One year ago, on November 12, 2014, the world held its collective breath as a washing-machine-size lander called Philae decoupled from its mother ship, Rosetta, and descended onto the alien terrain of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Now, the European Space Agency team that guided Rosetta and Philae through their historic exploration is preparing for the final year of operations.

Early ideas called for Rosetta to go into hibernation as the comet heads toward aphelion, then to awaken it when the comet and orbiter again approached the Sun in four years' time. But the team decided against this move, as the aging spacecraft would likely not survive another extended span in hibernation.

Artist’s impression of ESA’s Rosetta orbiter approaching Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

ESA / ATG medialab / Rosetta / Navcam

ESA / ATG medialab / Rosetta / Navcam

Instead, during 2016 Rosetta will assume a series of looping elliptical orbits around Comet 67P, culminating with a dramatic "controlled crash landing" on the nucleus next September. The team hopes to return data from Rosetta right up until the very end.

"Rosetta will, next year, continue the current wealth of scientific data from C/67P and, in particular since the comet passed perihelion, will follow the comet's activity to its complete end," says ESA Rosetta mission manager Patrick Martin.

The closest that Rosetta has come to the nucleus was 8 km (5 miles), when it released Philae last year for its 7-hour descent. Philae returned data throughout its plunge, only to bounce slowly across the surface like a beach ball before finally coming to rest in a hole.

An image taken by the Rosetta's OSIRIS camera captures a dust cloud where Philae first touched down on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko — as well as Philae itself in mid-air (and its shadow) as the spacecraft bounded away.

ESA / OSIRIS team

ESA / OSIRIS team

"We should be able to fly much closer than what was done last year, says ESA Rosetta spacecraft operations manager Andrea Accomazzo. "The idea is to go down to a 2 kilometre distance for a few weeks, and see how the comet has changed after perihelion passage."

Although Philae briefly awoke this past June and July and phoned home with a brief burst of data, a true two-way reconnection never really happened. It's possible the team might still release tidbits of those brief chats with Philae in the near future.

"Searching for Philae's precise location once imaging resolution is good enough will be an essential goal before the end of mission operations on September 30, 2016," says Martin. "Further contacts with Philae are possible this week, as the orbiter is getting close enough to the nucleus and over the northern latitudes, and will also be possible a number of times by the end of the year."

A Bittersweet Moment

Here's how asteroid 21 Lutetia looked less than 5 minutes before Rosetta's closest approach on July 10, 2010.

ESA

ESA

The story of Rosetta spans more than two decades, since the mission inception and approval in 1993. Rosetta launched atop an Ariane 5 rocket on March 2, 2004, then cruised for an amazing 10 years to arrive in orbit around Comet 67P. Along the way it made flybys of Mars and of asteroids 2867 Steins and 21 Lutetia.

Rosetta has revealed the bizarre realm of Comet 67P, a twin-lobed world of active water-ice jets, sinkholes, and more. One amazing revelation is just how dark the comet's surface really is, with an average albedo (reflectivity) of around 6½%, blacker than any Spinal Tap album — though the overall range of reflectivity is about 30%. (Are all comets this strange?)

So the decision to crash-land Rosetta represents the end of an era for ESA researchers and scientists who have spent decades on this effort. Expect to see some amazing close-ups of the nucleus during the final days of Rosetta.

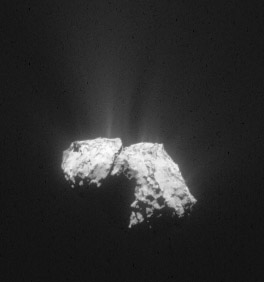

On September 10, 2014, Rosetta's wide-angle camera captured jets of gas escaping from the nucleus of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (overexposed). The comet became much more active as it approached perihelion in August 2015.

ESA / OSIRIS Team

ESA / OSIRIS Team

The spacecraft will descend in a much more leisurely fashion than Philae, and scientists expect to bring Rosetta's ROSINA (Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis) to bear to study gases released from the active comet. Similarly, OSIRIS (Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System) will have a bird's eye view on descent, with an expected resolution of better than 1 cm (0.4 inch) per pixel from an altitude of 500 m (1,500 feet) above the comet's surface.

"The final year of the mission is key, as it will provide us with a comprehensive idea of how the comet works as it moves away from the Sun," says astrophysicist and ESA project scientist Matt Taylor. "This aspect is a major goal of Rosetta — examining and comparing what we measured on the way in, versus what we see on the way out, really allowing us to dig deep into how a comet works."

Comet 67P/Churuymov-Gerasimenko was still active when imaged by Rosetta on October 18, 2015, some two months after its perihelion.

ESA / Rosetta / NavCam

ESA / Rosetta / NavCam

Just how long Rosetta will relay data prior to impact depends on aligning its descent with line of sight communications of the Earth. Even if it survives its expected impact with the comet — which, the engineers hope, will be measured in mere centimeters per second — the spacecraft won't be able to aim its communications antenna once permanently "grounded" or to align its solar panels for power.

So Rosetta will likely silently join Philae on the surface of Comet 67P as the second human-made artifact to strike the exotic comet, a fitting end to a daring and exciting mission.

-

No comments:

Post a Comment